“The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White” (1971, 1988) by James W. Loewen.Chinese labourers were imported into the American South after the Civil War to replace emancipated black slaves. The plan failed. Chinese importation halted after the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) and by the late 1880s, all had left the plantations.

Some Chinese left the South, mainly moving to the growing Chinatowns in the North. The Chinese-American population plummeted by 60% in the 1880s and 1890s, but New York City’s Chinatown actually grew from 200 in 1880 to over 7,000 by 1900 and continued growing afterwards.

Of those who stayed in the South, some migrated to larger cities, such as New Orleans and found work there. Some ran businesses (e.g., laundries) across the South. And some became grocers to black sharecroppers, a new niche of the post-Reconstruction South.

Joe Gow Nue Grocery Store in Greenville, Mississippi, 1930s

Sharecroppers bought food and daily necessities from plantation commissaries. The prices were inflated to keep them in debt. By 1880 in Mississippi a few Chinese opened makeshift grocery stores with very basic items, charging less than the plantation commissary. The commissaries began to disappear.

By the early 1900s over 95% of Chinese men in the Mississippi Delta were grocers.

Several factors caused this:

Blacks could not get credit or capital to open their own stores.

Whites would not open stores in black neighborhoods.

Most of the Chinese came from the same region of Guangdong province, speaking similar rural dialects and often sharing kinship ties. They could provide each other with training, credit, and access to distribution networks. Once one of them set up a store, another, perhaps a relative, could work in it, gain experience, save some money, and then open up his own store in a nearby town.

Chinese did not share close kinship ties with their most of their customers. They did not feel obligated to extend credit or loans to their customers (unlike a potential black storeowner, who would have many sharecropper relatives in debt).

Most did not have family and could live at their store.

By the early 1900s, a third of Chinese men in Mississippi had taken black wives, though most remained single. The Chinese Exclusion Act left Chinese males little prospect of bringing over wives from China, while anti-miscegenation laws put white and Mexican women out of reach (except for those who got themselves classified as “White”).Mixed Chinese-black children were categorized as “Chinese” in the 1880 census; in the 1900 census, most had been reclassified as “colored”, a few as “white” (especially if their mother was part white), but none as “Chinese”.

In 1906 the San Francisco Earthquake destroyed city records, making it hard to strictly enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act. “Paper sons” and daughters began arriving from China on forged documents.

By 1910, Chinese men in the Mississippi Delta had begun taking Chinese wives and formed families. These families would later challenge the Jim Crow laws popping up across the South.

By the 1960s, mechanization had replaced hand labour. Many towns lost over half their black population in the Great Migration. Their niche livelihood was drying up, and most grocery stores shut down in the 1970s. Few remain today.

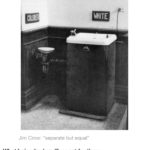

What being “colored” meant for them:

Employment: In the Mississippi Delta nearly all Chinese men became self-employed grocers to black sharecroppers, a niche whites did not want.

Marriage and family: Anti-miscegenation laws added “Mongolian” and “Malay” as races that could not marry whites. Meanwhile the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 made it nearly impossible to bring over wives or brides from China. Most Chinese men remained bachelors, though some married black. After 1910 “Paper Sons and Daughters” began to arrive from China, through a loophole in the Exclusion Act created by the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

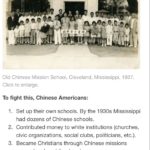

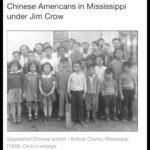

Education: In the 1920s their children were kicked out of white schools and forced to go to the immensely inferior coloured schools. Gong Lum of Rosedale, Mississippi took it to the Supreme Court. He lost: in Lum v Rice (1927) the Supreme Court ruled that any jurisdiction could classify a non-white group as “colored” as long as “equal” facilities were provided.To fight this, Chinese Americans: Set up their own schools. By the 1930s Mississippi had dozens of Chinese schools. Contributed money to white institutions (churches, civic organizations, social clubs, politicians, etc.). Became Christians through Chinese missions opened up by white churches. Had white people witness them mimicking whites in their treatment of blacks. It slowly took effect. Some churches closed their Chinese missions and let their congregations attend the white churches. Some districts could not afford schools for 3 separate races and eventually closed the Chinese schools. If one white school would not accept Chinese students, parents would send their kids to a school in another district. The acceptance to white institutions was not universal; it often depended on the whites in the local community. One Chinese group was left behind – those who married black or were part black. Whites made it very clear that in order to let Chinese into any white institution, they must guarantee that they were full Chinese with no “Negro” blood. By the early 1950s, the separate Chinese schools had closed and most Chinese children were attending white schools. Chinese had to work continuously to gain “white” status. Some contributed to the White Citizens Council to oppose segregation – while some also contributed to the NAACP to appease their black customers. They always had to walk a racial tightrope to please whites without offending blacks. They would be “white” for some things, but not for others. They could attend the white schools, but could not be valedictorian or date any whites. They were not always permitted to move into white neighborhoods. In 1954 Brown v Board overturned Lum v Rice. In 1967 Loving v Virginia overturned anti-miscegenation laws. By the 1960s, mechanization had replaced hand labour in the cotton fields. The Delta lost much of its black population in the Great Migration. With their customer base disappearing, most Chinese were leaving the Delta by the 1970s – after spending decades trying to be accepted as “white”.

Just another WordPress site