(These are notes from a lecture I gave a year ago to an intro media class, part of an introduction to the concept of the cinematic gaze. We were working with the basic ideas from Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” specifically, that women are the erotic objects of the gaze in cinema, both of the audience and the characters on screen, and that men are the bearers of the gaze, owners of the pleasure, knowledge, and power it gives. Men look, women are looked at: the camera looks with the eyes of a het man, and the audience looks with the eyes of the camera. Sherlock turns out to be an interesting test case for these ideas. As both the object of the erotic gaze and the subject of the knowing one, he puts a spin on Mulvey’s model. Please note that people have critiqued and developed these ideas a whoooole lot since she wrote; again, this was an explanation and illustration of the basic questions. And I’m pretty sure mid0nz has made similar observations; check her metas for more.)

Part One: Watching the Detective

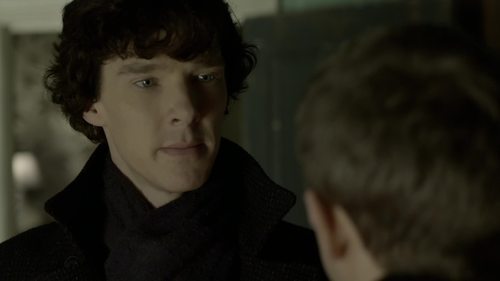

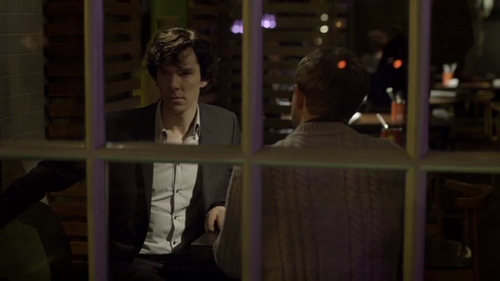

Like any detective story, Sherlock is all about looking: “you see, but you do not observe.” It’s all about the knowing gaze, the desiring gaze—the gaze that desires to know. Within the story, Sherlock’s the bearer of this observant look, and it’s his searching scrutiny that moves the narrative along. But the most frequent object of the viewer’s gaze isn’t the crime or the criminal, it’s Sherlock himself. The camera almost begs us to look at him, especially when he’s deducing. In “A Study in Pink,” Paul McGuigan uses a great many of the techniques that have traditionally been used to make women the object of visual pleasure in film to focus us on Sherlock and make us enjoy the view. The camera makes sure we take pleasure in looking at him. He’s continually foregrounded, beautifully dressed and lit, looked at by others (mostly men) on screen, and sometimes just straight-up sexualized.

As we see in the last image, McGuigan also cues us to look at him with others on screen. In one of his favorite framings, we look at Sherlock with John, over John’s shoulder. (John, like ACD’s narrator Watson, is our point of identification within the story, the mediator between us and Sherlock. We see—and love—Sherlock along with John.)

Just another WordPress site