hey, where can I watch Hamilton? I keep seeing gifs everywhere, but I can’t find a video

hi! so there’s no video of the full show right now, bootleg or otherwise. so, unless you’re able to get tickets to see it in new york, you’re out of luck. :/ all of the gifs going around are from these videos:

“Hamilton”: A founding father takes to the stage (interview w/ lmm + some short clips from the show)

HAMILTON Montage (Off-Broadway)

Hamilton B-Roll (ten minutes of clips from the show)

Burn

… Is it bad that I have been vaguely wondering whether you had writing thoughts about Aaron Burr ever since “I AM THE ONE THING IN LIFE I CAN CONTROL”?

…the only bad thing about that, anon, is that I am becoming PREDICTABLE and therefore can no longer surprise my enemies, I guess.

the first time I heard that line I probably stopped dead on the footpath/in the middle of cooking/whatever I was doing, and probably said “YES” aloud. followed by learning very quickly the rhythm needed to bawl along to “I AM INIMITABLE, I AM AN ORIGINAL”.

by most theatrical tropes (including where in the musical it’s placed), ‘wait for it’ is THE VILLAIN MONOLOGUE. it’s scar, growling be prepared.

but my favourite thing is that it’s NOT a straightforward song, and its meaning changes in retrospect. sure, by the time you hit it, you’re so much on hamilton’s side that it comes off as burr being overly defensive of his sitting-on-his-hands attitude. so as an audience we’re a bit predisposed to be thinking: what DO you stall for, aaron? why aren’t YOU throwing yourself headlong at life? this is WHY nobody is inviting you into the room where it happens! get a grip, man! take a risk!

and–as someone who agonises over her lack of productivity, and for whom the line you mentioned smacked me firmly in the gut–I heard it as a PERSONAL REBUKE. stop waiting. start writing. like you’re running out of time.

(aaron burr is every child who grew up searching for a meaning to their loss, deciding that there HAD TO BE A MEANING, and that if they just learned the rules well enough–learned how not to be offensive, how to be SAFE–then life would finally give them what they wanted. if you are the only thing you can control, then your control has to be perfect. life is dangerous. don’t leap. watch. watch. watch some more.

hamilton is the child whose loss taught him to grab hold of everything, right now, RIGHT NOW, because at any moment it could be snatched away.)

but the whole point of the musical is that burr’s approach isn’t actually WRONG and neither is hamilton’s, but they are such opposites and so firm in their personalities that they can’t help but be bewildered by the other. and that inability to find common ground (I will never understand you) is what eventually turns into anger. the tragedy is that both of them are hamstrung by their failings.

& in the end we’re left with burr having FINALLY REALISED that the musical’s entire message is in direct opposition to his driving philosophy: you have no control.

history obliterates; it paints me with all my mistakes.

but when ‘wait for it’ hits, AT THAT POINT IN THE MUSICAL, we don’t know that. we just have aaron burr’s furious rebuttal: I’m not standing still; I am lying in wait. and he is speaking to us, the audience. he knows we’re not on his side. he knows he’s the villain in our history.

jkdfhdjkhash I guess you could say I have some feelings about aaron burr

I guess you could say that

Friend: why is everyone suddenly thirsty for Alexander Hamilton’s dead ass?

Me: because he’s young scrappy and hungry and HE’S NOT THROWING AWAY HIS SHOT

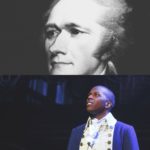

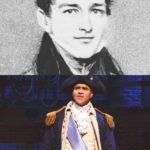

For the central character of Alexander Hamilton, Tazewell thought, “He needs to look like he is coming from some place else and not completely formed as a man at the beginning. Then he goes into uniform with the American army, and after the war, he shifts into the color green, the color of money, until his son passes away, and then we wears black at the end of the show, as his priorities shift.” In terms of historic accuracy, Tazewell made use of it in a poetic way, using the green color to always pull Hamilton out on stage. “He was known as someone who dressed above his station,” adds the costume designer, who also dressed Hamilton in suits of silk and wool.

Aaron Burr is more conservative, according to Tazewell, “playing it safe and then becoming the antagonist. It was important to keep his look lean and dark, so he goes from uniform to deep charcoal gray to black, with an eggplant vest. This holds Hamilton and Burr in contrast, until the end when they have the same black coat and approach one another as equals, and it becomes an everyman story.”

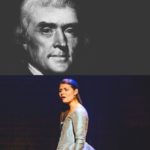

Thomas Jefferson had the biggest change, color-wise, from The Public to Broadway. “The shape is the same, but we made him more of a rock-star figure, with his costume going from Jeffersonian brown to magenta, like Jimi Hendrix or Prince. His suit is made of silk velvet and silk Duchess satin,” explains Tazewell.

In collaborating with Binkley, Tazewell notes, “There were some color shifts with the sisters’ dresses in moving to Broadway when I knew Howell was going to use more color to help pop their costumes more. For all of us, going to Broadway and looking at the detail of what we had done at The Public, this was a chance to make it more perfect and more specific. I’d say to Howell, ‘Please tell me if there is a color that isn’t correct, and we can shift it.’ I know I can go to him and ask him to adjust something up or down if it affects a costume. We didn’t have that issue here. It’s great to have a shorthand that is so effective.”