French princess Isabella was only 12 years old in 1308 when she sailed into the court of English king Edward II as his wife. And he, the 24-year-old freshly crowned monarch, was very much in love … just not with her. The person Edward was in love with was a young knight named Piers Gaveston. That Edward had a lover wasn’t shocking, nor was it a big problem that his lover was a man. The problem, as the English court saw it, was how “immoderately” Edward loved the glamorous, arrogant Gaveston— enough to risk his entire kingdom and the lives of thousands of soldiers. When Gaveston was around, Edward was worse than useless, barely able to hold a conversation, much less govern. When Gaveston wasn’t around, Edward was a wreck.

While Edward and Isabella were married in France, Gaveston stayed in England with his own child bride, Edward’s 15-year-old niece. Less than a month later, Isabella witnessed firsthand just how deep the man’s hooks went into her husband’s heart. During the ceremony at Westminster Abbey investing Isabella with the title of queen, it was Gaveston who held the crown. At the coronation feast afterward, he sat next to the king under tapestries that depicted not the emblems of Edward and Isabella but the arms of Edward and Gaveston. And just to turn the dagger a bit more, Edward handed over the wedding gifts from Isabella’s father— jewels, warhorses, the whole lot— to his one true love. Isabella’s uncles, who had attended the coronation, returned to France in a frothy rage. Which was bad news, given that France and England were perpetually squabbling and barely maintaining an uneasy truce. England was already embroiled in a conflict with Scotland and didn’t need another front to open up. England’s powerful magnates— the lords and earls who really ruled the land— decided that Gaveston was too great a distraction for the king and needed to be removed. But attempts to exile the king’s favorite proved futile. Edward would send Gaveston away and then, a few months later, call him back.

Their frustration with Edward reached a boiling point in 1312; civil war was in the making. Edward and Gaveston traveled the countryside, trying to keep ahead of the lords baying for the latter’s blood, but they couldn’t run for long— England is only so big. On May 19, Gaveston surrendered to the king’s enemies at Scarborough Castle, where Edward had left him ensconced with a battalion. Just over a month later, Gaveston was executed, brutally and without a trial. The king swore he’d have his revenge.

Isabella, meanwhile, was biding her time. She’d become an adult while following Edward and Gaveston around the country; at the time of Gaveston’s execution, she was pregnant with her husband’s son and heir. On November 12, 1312, the 17-year-old queen gave birth to a healthy baby boy. She’d done her duty to crown and husband, and her position was secure. She had also accumulated enough political acumen to manage her useless husband and try to keep the nation from civil war. Edward and his warring lords patched things up long enough to sign a peace treaty, which got them through the first few months of 1313 without killing one another. With Isabella’s mediation, the lords swore fealty to Edward once again, but it was a tenuous peace. The Scots were hammering England’s defenses to the north, and Edward’s most powerful earl (and the man responsible in part for Gaveston’s murder), a man named Lancaster, refused to aid him. Worse, Lancaster was actively plotting against Edward while England was left rudderless, without a real leader.

Isabella remained at Edward’s side, his confidante and advisor. That is, until about 1318, when Edward again became infatuated with a young man in his company. Unlike the foppish Gaveston, Hugh Despenser was shrewd, cruel, and paranoid. He used the royal relationship to seize his rivals’ lands and treasuries. As Despenser hoarded more gold and more land, more and more lords began defecting to Lancaster’s side. Isabella worked to maintain peace between her husband, his magnates, and an irate France, but they all demanded that Despenser be exiled. In July 1321, Edward gave the order; ever the sly one, Despenser went only as far as the English Channel, where he and his father turned to pirating merchant ships while awaiting word from Edward. Meanwhile, the king’s struggles with Lancaster came to a head. Lancaster found himself on the losing side of the battle; he was arrested and executed as a traitor. Edward had his revenge.

Edward may have won a battle, but he was about to lose the war. Triumphant after Lancaster’s death, he hastily called the Despensers back to England and made Hugh his chief advisor. Ever the opportunist, Hugh then started to make moves on Isabella’s property and that of her children. Bad decision.

Hell hath no fury like a woman whose children’s birthright is in danger. Now a seasoned political manipulator, Isabella waited for just the right moment to act, and in 1325 opportunity finally landed in her lap. By then, England’s relationship with France had frayed over land that both claimed to rule. It was decided that Isabella was ideally suited to work out a solution with her relatives back home. So the queen (who had likely planted the idea with Edward and Despenser) made her way back to France, where she spent several restorative months in the bosom of her family. Six months after landing in Calais, she was followed by her son, 12-year-old Prince Edward, on the pretext that relations between France and England would be softened if he were made duke of Aquitaine. And just like that, 27-year-old Isabella held the trump card: the heir to the English throne.

Within weeks, Isabella showed her hand. “I feel that marriage is a joining together of man and woman … and someone has come between my husband and myself trying to break this bond,” she said in a statement. “I protest that I will not return until this intruder is removed.” Edward was gobsmacked. “On her departure, she did not seem to anyone to be offended,” he supposedly remarked. Isabella’s plan was ingenious and subtle. Her husband was a useless king, but she couldn’t say so without looking like a traitor. So she cleverly shifted the blame to Despenser and cast herself as the dutiful wronged wife. Isabella also knew that Edward was unlikely to be a worthy leader even if Despenser were removed. Lucky, then, that she happened to have an alternative ready to roll and under her control: her son, the prince.

Isabella had spent the last six months getting all her ducks in a row. Not only did she have France on her side, she had also won the loyalty of a faction of disaffected Englishmen to legitimize her rebellion. They were led by Roger Mortimer, one of the nobles who had led the revolt against Edward. Two years earlier, Mortimer had made a daring escape from the Tower of London and turned up in the French court. He and Isabella met up in Paris; he became not only her captain, but her lover as well.

To get her son on the throne, Isabella needed military might, so she and Mortimer engineered a marriage between young Edward and the daughter of a French count. In late September 1326, Isabella and Mortimer set sail for England with her daughter-in-law’s dowry— 700 soldiers— along with a pack of mercenaries paid for by Isabella’s brother, the king of France. Isabella was, without a doubt, at the head of this operation; one fourteenth-century image shows her leading the troops while clad in shiny armor. Popular support for her as a romantic, righteous figurehead had been growing since word of her rebellion spread; that support, and her ranks, continued to swell after she returned to English soil. Edward had fallen out of favor not only with his lords and magnates but also among his people, who had suffered famine and war while he was occupied with avenging his lover’s death.

The end came swiftly. On November 16, the king and his companion were caught trying to make it across open country in Wales. Hugh Despenser was brought before the queen and her lords and sentenced to death. He was dragged through the streets, stripped naked, and hauled 50 feet in the air by his neck. He was then disemboweled while alive and castrated— punishment, it was rumored, for his intimate relationship with the king. As if all that wasn’t enough, he was beheaded, too.

The king was confined to Monmouth Castle as a prisoner of Henry of Lancaster, brother of the rebellious earl whom Edward had executed four years before. But Isabella and Mortimer still had one problem: with Despenser gone, the dynamic duo no longer had reason to challenge Edward’s fitness to rule. So, clever Isabella argued that, by fleeing to Wales, Edward had abandoned England and his right to rule it. Prince Edward was, therefore, the rightful king. The relieved bishops and lords of England agreed. Now all that remained was to convince Edward to resign the throne in favor of his son. Faced with overwhelming opposition, he agreed, and Prince Edward, just 14 years old, became King Edward III on February 1, 1327. Isabella, as the mother of the underage ruler, and Mortimer, as leader of the deposing army, now held authority in England.

The situation was unprecedented— it was the first time the country had ever had a living ex-king. And there was also the issue of Isabella’s marriage: Edward may have been an ex-king, but he was not her ex-husband. With Despenser gone, she had no legitimate reason not to return to him. Moreover, Edward’s very existence posed a threat to the new regime, especially since it appeared he wasn’t completely without supporters. Indeed, by September 1327, three plots to free him had been foiled. So the queen and her captain hit upon a more traditional means of ridding themselves of this troublesome ex-king: murder.

The story is probably apocryphal, but later chroniclers morbidly insist that Edward II was murdered by the violent application of a red-hot poker up his backside. However death occured, on the night of September 21, 1327, the 43-year-old relatively robust former king conveniently died. He was buried with all the ceremony accorded to a dead monarch, his wife and son weeping and kneeling before his gilded hearse.

But young King Edward III, it seems, had learned a trick or two at his mother’s knee. Though Isabella and Mortimer were content to run things in England indefinitely, Edward wasn’t about to sit idly by and watch them do it. In late 1330, just three years after Isabella and Mortimer seized power, the 18-year-old king outflanked them. Mortimer was arrested as a traitor by a group of nobles loyal to the crown; he was hung on November 29, 1330. Isabella had but one choice: accept the death of her lover and an enforced retirement, surrendering her vast estates to her son. Ever the realist, she did so within a week of Mortimer’s execution. Isabella lived the rest of her life in quiet obedience to her son, dying in 1358. The “She-Wolf of France,” as she came to be called, was buried as she requested: with a silver vase containing the heart of her husband, the man she’d kicked off the throne and probably murdered.

Princesses Behaving Badly: Real Stories From History Without the Fairy-Tale Endings

(via leslieknope)

I love it when royalty makes murder look like your average HBO shows.

(via hemlockian)

Roger Casement, Arthur Conan Doyle, and His Last Bow

Roger Casement was a friend and correspondent of Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle based a character in The Lost World on Casement, and Holmes’ last case, “His Last Bow,” was influenced by Casement, as well. Casement’s life as civil servant, human rights advocate, convicted traitor, and ultimately, “infamous” homosexual had a powerful influence in Edwardian England.

Roger Casement was knighted for his role in exposing disgusting mistreatment of forced laborers on the Congo, and his 1903 Casement Report was instrumental in removing the colony from the personal control of Leopold II of Belgium. Casement went on to expose abuses in Peru as well.

Casement was Irish, and a passionate advocate of Home Rule—so passionate, he collaborated with Germany against Great Britain in an effort to overthrow English rule in Ireland. The effort failed. Casement was convicted of treason and stripped of his knighthood, then executed.

Casement had always passed as straight and normatively masculine, but during his prosecution for treason, it emerged that he had also kept diaries detailing his long record of anonymous sex with working-class British and native prostitutes and strangers in public places. These “Black Diaries” were found and manipulated by the British Government, who showed them to Casement’s supporters during the trial and aftermath to weaken support for him. And indeed, many did back off from their support for the former national hero when faced with first-hand accounts of his “depravity.”

Significantly to the British government’s smear campaign, Casement wasn’t just queer—he was a “bottom.” (This element of his sexuality was so important to the case for Casement’s depravity and dehuminization that after his execution, a medical exam confirmed it from an examination of his anus and this report was circulated.) Casement’s diaries were cursory—but often included the measurements of the size of his penetrators’ penises. These were the excerpts circulated among journalists and Casement’s supporters—Conan Doyle included—in efforts to influence opinion against him even in (Catholic) Ireleand.

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote the unsuccessful letter that argued against his execution on the grounds that Casement was mentally unstable and further that martyring him would harm the British cause. Doyle saw the Black Diaries as further evidence of mental illness. This argument failed and Casement was executed in August 1916.

In Sherlock Holmes last (chronological) case, we find he has been “passing” as an Irish American member of Sinn Fein, pretending to sell military secrets to Germany in an effort to support The Irish rebellion. The case, set-up, and even the anti-British statements Holmes makes as “Altamont” directly echo Casement’s trial. Altamont, furthermore, was the name of Doyle’s father (himself a patriot).

The end of the story closes on a famously propagandistic, pro-English note. But, Holmes closes his career “passing” as a character based not only on a traitor, but on a man publicly exposed as a more notorious homosexual even than Oscar Wilde. “it’s complicated.”

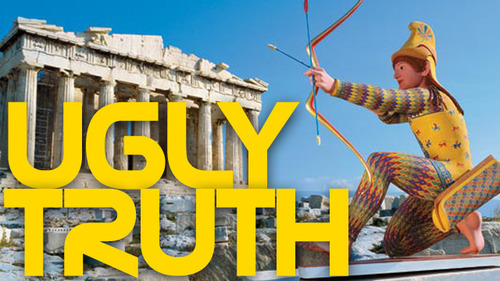

re: chromophobia… of course these chromophobes idolized a Greek/Roman past full of cool white marble…. which we’ve since discovered was actually a gaudily painted riot of color!

I always love seeing this fact pop up. Yeah, what we thought was the ancients just being really cool and aesthetic was actually the gaudy colors fading away over time. It’s like when people think that old houses were built better than they are now, when it’s really just that the shitty houses all fell down already.

Ummmm but the problem is not so much that they weren’t being “cool and aesthetic”; it’s that this entire western concept of aesthetics is built on a mistake.

The ask was in response to this article, which makes it 200 times funnier.

fittingly, I was just reading this:

The Parthenon marbles Elgin took to Britain do consist of marble, but a darkly pitted Greek marble rather than the smooth, snowy white variety more common in Italy. Here lay an aesthetic problem: whiteness versus color. The alarming history of European marble “cleaning” includes a chapter on this statuary describing a drive to make ancient Greek art white that nearly destroyed the art itself. In the 1930s workers in the British Museum were directed to remove the dark patina with metal tools on the mistaken assumption that their proper color should be white. Such a “cleaning” seriously damaged the Parthenon marbles, prompting an inquiry by the museum’s standing committee that halted the work.

—Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People, page 63

It’s particularly obnoxious given the claims by so many British people that the marbles had to be removed to Britain in order to protect them.

The bold: People should really know about that, too.

And yes, it is connected with this article about Chromophobia and colonialism

which is also connected to the Reformation.

Especially if you think about (at least in an American context) the way that Catholicism has been, to a large degree, racialized. And how the Catholic Mass and other traditions came to be associated with licentiousness and was condemned for its use of decoration (aside form legitimate gripes with corruption).

see also: Calvinist Iconoclasm:

OMG!!! I FORGET PEOPLE DON’T KNOW THIS!

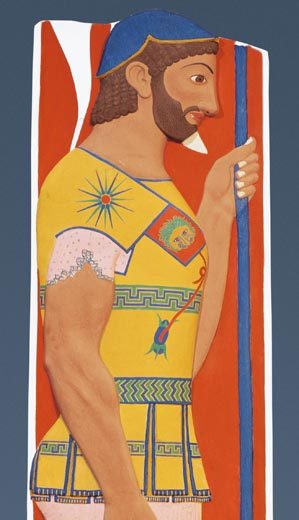

Yes, all those aloof, “pure” white statues from Ancient Greece?

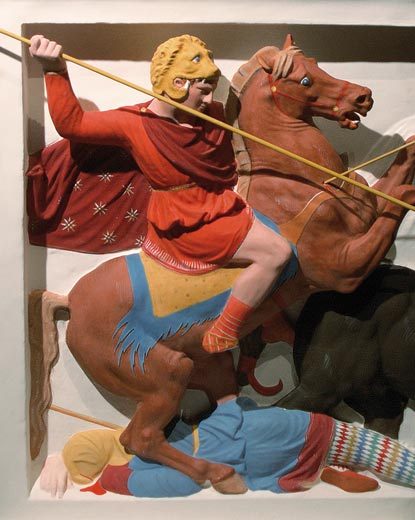

They actually looked like this:

Vinzenz Brinkmann, much to the apparent chagrin of Westerners everywhere, used ultraviolet light to reveal the original paint schemes of these statues that the millennia had washed away.

And to underscore the Chromophobia?

Check out this graphic that i09 made for their leading image for this story:

In the summer of 1566, spurred on by the sermons of Calvinist preachers, zealous mobs descended on churches in the Netherlands, intent on ridding them entirely of their imagery. Many churches were literally white-washed.

All of these things are connected.

reblogging for someone who recently asked about this.

Someone also asked about over-cleaning or modifications made to various Greek and roman works in European Possession.

British Museum: Over-Cleaning of the Elgin Marbles

British Museum: Public Response

Like, they were literally dipping them in acid to make them “pure and white” as they imagined they were “originally”.

Medieval churches in England also suffered from a similar problem. Originally they were covered in murals, floor to ceiling, in the gaudiest colours they could manage. Part of it was probably to engage the illiterate population with a giant devotional picture book.

Here’s a snippet from one I studied in the Deanery of Durham Cathedral:

Then along came the Reformation with its accusations of idolatry, its desire for direct book learning for everyone and its general drive to

make everything boringremove the distractions of the material world.In some churches, they chipped the images off the walls, but in many they just white-washed over them.

Which would be fine for us, since layers of white-wash can be removed to reveal the original paintings, as happened in the Deanery and as happens around the UK by accident on a regular basis, where the old white-wash is still in place.

But alas, the Victorians happened. They saw the bare stones of the thoroughly defaced churches and thought they had more grandeur than the white-washed or ,worse, the still painted churches, and so set about ‘restoring’ the churches of England.

Granted, compared to the art of the renaissance and the classical greek world, the English medieval murals do look like crude kiddy scribbles, offensive to the Victorian (and modern) sense of taste and not at all what they wanted in their monumental architecture. But they were the medieval decoration, like it or not.

‘Victorian Restoration’ is a well-known oxymoron in old architectural nerd circles. The walls of many churches were stripped back to the stone and in some cases, beyond. The entire outer surface of Durham Cathedral was chipped off (I forget the exact depth, some small number of centimetres), to make it ‘clean’.

But yeah, prior to the Reformation, the British Isles loved colours. There were the sumptuary laws, in which the nobility tried to keep the wearing of awesome colours to themselves when rich commoners started to get in on the deal. There were the bardic rules in Ireland, where the higher rank a bard you were, the more colours you got to wear. And then there was the amazing rivalry between blue dye merchants and red dye merchants (you know why devils were painted as red? Because the blue dye merchants were slandering the red dye merchants.)

But alas, the Victorians Happened=best paragraph intro since everything changed when the Fire Nation attacked

For years, I opened my 11th-grade U.S. history classes by asking students, “What’s the name of that guy they say discovered America?” A few students might object to the word “discover,” but they all knew the fellow I was talking about. “Christopher Columbus!” several called out in unison.

“Right. So who did he find when he came here?” I asked. Usually, a few students would say, “Indians,” but I asked them to be specific: “Which nationality? What are their names?”

Silence.

In more than 30 years of teaching U.S. history and guest-teaching in others’ classes, I’ve never had a single student say, “Taínos.” How do we explain that? We all know the name of the man who came here from Europe, but none of us knows the name of the people who were here first—and there were hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of them. Why haven’t you heard of them?

This ignorance is an artifact of historical silencing—rendering invisible the lives and stories of entire peoples.

[…] In an interview with Barbara Miner, included in Rethinking Columbus, Suzan Shown Harjo of the Morning Star Institute, who is Creek and Cheyenne, said: “As Native American peoples in this red quarter of Mother Earth, we have no reason to celebrate an invasion that caused the demise of so many of our people, and is still causing destruction today.” After all, Columbus did not merely “discover,” he took over. He kidnapped Taínos, enslaved them—“Let us in the name of the Holy Trinity go on sending all the slaves that can be sold,” Columbus wrote—and “punished” them by ordering that their hands be cut off or that they be chased down by vicious attack dogs, if they failed to deliver the quota of gold that Columbus demanded. One eyewitness accompanying Columbus wrote that it “did them great damage, for a dog is the equal of 10 men against the Indians.”

Corporate textbooks and children’s biographies of Columbus included none of this and were filled with misinformation and distortion. But the deeper problem was the subtext of the Columbus story: it’s OK for big nations to bully small nations, for white people to dominate people of color, to celebrate the colonialists with no attention paid to the perspectives of the colonized, to view history solely from the standpoint of the winners.

Bill Bigelow, Rethinking Columbus: Towards a True People’s History

Just your random reminder that this is a banned book.

In January of this year, district officials came into Tucson’s high schools, confiscated the offending books, put them in boxes, and carted them away. These books were taken while classes were in session, so that the teachers and students wouldn’t miss the point.

What’s even more terrifying is that their actions were in compliance with an Arizona state law.

HB 2281 has terminated Tucson’s Mexican American Studies program, a virtually one of a kind social studies and humanities high school program that seeks to close the “achievement gap” by encouraging Tucson students (of whom at least 60% are Latino) to look at American history critically in regards to race, gender, and ethnicity.

But Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction John Huppenthal will have none of it, and threatened to withdraw 14 million dollars in state funding to the Tucson Unified School District if it failed to comply with the law, which criminalizes, among other things, “any courses or classes that…advocate ethnic solidarity…”

And so hundreds of students have had their curriculum literally snatched away from them at mid-year; their teachers are now required by law to assign them more “traditional” reading material that ignores the racial, gender, and class biases that have so tragically shaped our country.

Another gentle reminder that there are *ahem* various places I could be arrested for teaching this to you in school.

(via abandonthefort)

This is just like in the Palestinian territories where teachers are banned and can be sanctioned, fined, or imprisoned by the Israeli government for teaching significant events of Palestinian history like the nakba.

(via tevelum)