Voyager is so happy, because it’s the bravest satellite of all. It has gone the furthest. And it’s not lonely, because it’s talking to us. It phones home. And it tells us all about the wonderful things that it’s seeing. …There’s a whole universe to explore, and it’s just leaving our Solar System right now. It’s very brave and very lucky to be doing what it’s doing, so it’s not going to get lost. It’s traveled further than anything we’ve ever built has traveled before. It’s actually showing us the way. …

It might have been safer for it to just stay home, and stay inside a building, but then it would have been sad forever, because it never would have done its purpose. It never would have discovered things. It’s all a wonderful story of great discovery and success, and it couldn’t have happened if Voyager hadn’t been brave…

It’s not really the fact that everything always has a start and an end, it’s what happens in the middle that counts. What do you while you’re alive? What do you do while you’re laughing? And I think we’re doing exactly what makes Voyager joyful and as happy as it could be.

Think about the fact that you’re a little bit like Voyager. In that you’re going to go see the world, and you’re going to call your mom on the phone and tell her about the wonderful things that you see. … You wouldn’t want to spend your whole life hiding under your bed and never seeing anything in your whole life, you want to be able to do what makes you happy and joyful and learn about things to discover. You might be the person that discovers something really important for everybody else on the world, but you can never discover that if you just hide and only do things that are safe. So think about yourself a little bit like Voyager. What makes you laugh? It’s not just staying, hiding underneath your bed safely at home.

Cmdr. Chris Hadfield, reassuring a five-year-old who was worried about the Voyager satellite (source)

Q: Girls are discouraged? That sounds so 1970s.

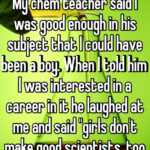

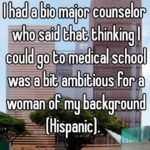

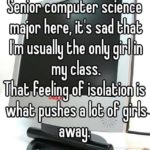

A: There was a 2001 study that showed in fourth grade, 68% of boys and 66% of girls like science. Starting in sixth, seventh and eighth grade, we lose girls and boys, but we lose more girls and for different reasons: lingering stereotypes, societal pressures. It’s well known that many girls have a tendency to dumb down when they’re in middle school. Just last week, I was talking to senior executives, and a woman told me that she was the best biology student in high school and had the highest exam scores. At the end of the semester, a teacher told her: “I’m sorry, but I’m going to have to give the award in biology to a boy, because it’s more important to him.” Almost every time that I give a speech or meet with a group of women, I’ll hear such stories.

Q: Boys earn 70% of the D’s and F’s in school and account for 80% of dropouts. Shouldn’t we fear more for their future?

A: It’s a big problem. Women earn the majority of undergraduate degrees in the U.S. and last year earned more Ph.D.s than men. But keeping girls in the science and math pipeline is a separate problem with different causes. It’s important we address both. You don’t stop research on breast cancer just because heart disease is also deadly. You work on both.

Q: Suppose you were an executive of a corporation that needs engineers. You meet a girl in high school. She scored in the 99th percentile in math on her SATs, yet says she wants to major in psychology or go to law school, because those careers sound more interesting. What do you tell her?

A: I’d introduce her to the coolest female engineer in the company. Girls tend to have a stereotype of engineers being 65-year-old guys who wear lab coats and pocket protectors and look like Einstein. Try to make it personal to them and show them some of the cool things that they can do in engineering.

Q: Let’s talk Lawrence Summers. The Harvard president recently resigned after giving a controversial speech a year ago suggesting that men might simply be predisposed to be better at math and science. Is there at least a grain of truth in what he said?

A: (Laughs). Suppose you came across a woman lying on the street with an elephant sitting on her chest. You notice she is short of breath. Shortness of breath can be a symptom of heart problems. In her case, the much more likely cause is the elephant on her chest.

For a long time, society put obstacles in the way of women who wanted to enter the sciences. That is the elephant. Until the playing field has been leveled and lingering stereotypes are gone, you can’t even ask the question.

Q: I will anyway. There are many obvious biological differences between men and women. This can’t be one?

A: There are obvious differences, but until you eliminate the more obvious cause, it’s difficult to get at the question scientifically. Look at law, medicine and business. In 1970 — that’s not ancient history — law school was 5% female, med school was 8% and business school was 4%. You could have taken a look at those numbers and concluded that women don’t make good lawyers or doctors. The statistics might have supported you. But today, all of those fields are about 50-50.

Public understanding of science is more central to our national security than half a dozen strategic weapons systems.

Skip ahead to 1:01 it’s not letting me embed it at that point

Very Important. The last five minutes of this panel, it’s asked if genetic differences might explain why there are fewer women in science. Watch Neil Degrasse Tyson explain very quickly and succinctly that it’s about society and expectations and the people in power.

Also the old white dude asking the question? Former president of Harvard and Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers

(via upworthy)

Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science? – NYTimes.com

Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science? – NYTimes.com

Hint: The answer has more to do with “The Big Bang Theory” than longstanding theories about men’s so-called natural aptitude.